Thursday, 14 May 1998

The crossroads where I’m at right now is on the one hand to be like a fart – to smell bad for a little while before I disappear into nothingness. On the other hand, I can take on the challenge that lies ahead of me: to settle my account (in a manner of speaking) with the establishment, and then to have the freedom to choose where, how and on what terms I will have a relationship with this establishment.

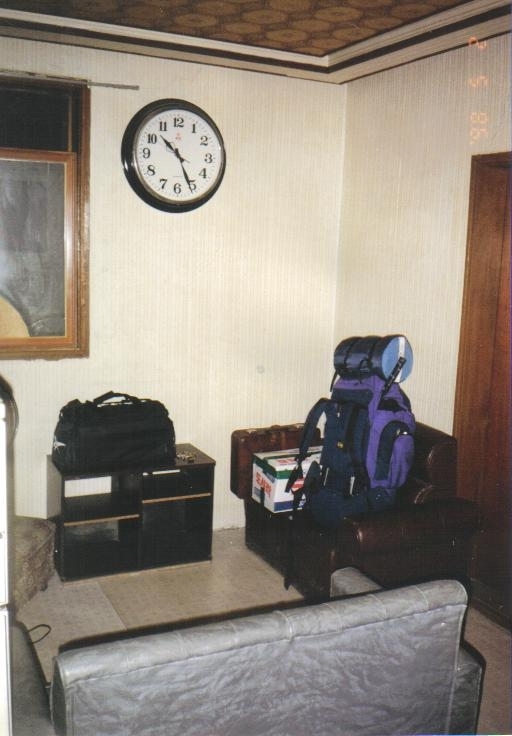

Wednesday, 27 May 1998

It’s my fourth week back in South Africa.

One aspect of my planning in Korea where detail was somewhat scarce was the so-called entrepreneurial projects. What was this supposed to mean? I knew it was a weak point in my planning, but I figured once I got home, I could talk to people who know more about these things.

It’s three weeks later. What I found out so far confirms what I suspected. In fact, if you are serious about making money – what I figure most people are not, there are more than enough books available about everything you need to know.

In short, if you believe money gives you power, and you’re desperate enough to get this power, the road you have to take is not some secret, known only to a blissful minority, over-grown footpath. It’s a well-traced route, but one I believe most people – who have the potential to take it – don’t opt for, for one reason or another.

One problem is getting a project going and developing it to such a point where it makes money you need at least a few months. There are of course projects that can give you an income faster, but once again it takes time to think of such a project.

Fact is, you can’t go into a kitchen and think you’re going to cook up a masterpiece just because you’re hungry. Even the best chefs need certain things: the right ingredients (money), a good recipe (methods, concrete plans or specific projects), and time – if the chef doesn’t have enough time, the final result will either be raw, or it will simply fall apart.

What do I suggest? It’s possible to launch a successful project in less than six months, but from the outset, I have to be prepared to spend at least that much time on research and preparation. I should also be financially prepared to meet all my needs for at least six months.

A plan of action: A good plan today is better than a perfect plan tomorrow. I have to formulate a Plan of Action for Today, considering Today’s Situation, Today’s Problems, and Today’s Needs. I have to reconsider everything I’ve said before, and reassess everything considering the knowledge I have about my situation today.

I’m not going to summarise several months’ worth of deliberations here. Suffice to say I’m still looking for the same thing, namely the ability to make choices and to take action. How I’m going to attain this ability is just a means to an end.

In terms of commitment to a means – let’s call it for arguments’ sake a “plan” – I can say that I am not currently working on a specific idea. It could be said that I am in a transitional phase between Korea and the Next Plan. That’s what I’m doing right now. I am working on the Next Plan.

[This piece is one of the reasons I had come so close to leaving Taiwan and returning to South Africa between 1999 and 2004 without ever doing it. I dreaded that moment where I would find myself sitting at another person’s kitchen table again, writing this type of journal entry.]

____________________